On this week’s post I’ve discussed fairness regarding the rules; let’s take this a step further and talk about agreeing upon made-up things.

Here’s the thing: The game’s world doesn’t really exist, which means everything we think about it is an opinion, not a fact (facts are things that exist). We tend to establish some general fictional facts, such as “my character is a Maseian”, but unlike in the real world – where, in case we want more details or clarifications, we can just check, or do some science and discover what’s real – the details of this fact don’t exist unless we invent them.

What does it mean that you’re Maseian? To you, it might mean X, and so, you immediately invent in your imagination some details that fit X; but for me, it might mean Y, and the details that I attach to Y aren’t the same as those that you attach to X.

This isn’t, usually, a problem, as long as we’re discussing facts that are “in the background” (for flavour). But when the facts have to do with what’s happening in the story – and especially if it’s an event that involved everyone – non-synced facts can lead to possible pitfalls that we should try to avoid.

Generally speaking, consider this: Because the fictional world only exists in our minds, there’s a different instance of it in each of our heads. These instances can’t be exact because we’re different people with different worldviews and backgrounds, which influence the automatic connotations we attach to each and every fictional fact we’re told (or invent) about the game world. Conflicts arise when you decide upon an action based on your instance, in a way that isn’t compatible with my instance. Misunderstandings will happen. The question is, how to handle them.

Let’s Take an Example

GM: The precious gem is inside the building. How do you get it?

Joe: I’ll climb to the second floor, and–

GM: What second floor?

Joe: Didn’t you say the buildings in this city are all Italian style?

GM: Sure, they’re white and clean, and–

Joe: Have several floors.

GM: I didn’t mean that!

How to deal with this?

Note that all of the following suggestions are aimed at players and GMs alike.

Prevention

It’s always better to try and prevent the problem, if possible. When you describe something using non-specific descriptors, words that are very general and can be interpreted in a variety of ways (“Italian”, “dangerous”, “old”), stop for a moment to elaborate on it and to allow other people around the table to ask questions or remark upon it, until you all nod in agreement.

GM: You walk down the streets of the city, the buildings around you are all Italian-like in appearance. Like, really white and clean.

Joe: Several stories tall, with flat roofs, right?

GM: Oh, are Italian houses like that? Well, yeah, sure, some have several floors, but most don’t.

Joe: Got it.

Is it important

When a misunderstanding happens, first ask yourself if the details are at all relevant to what’s happening in the story, and if so, how much. Insist on your interpretation only as so much as it actually matters to the game, not just to your own visualisation of the story. Players, note #4b: your personal story is not the main story. GMs, “Yes, and” this if possible.

GM: Sure, they’re white and clean, and–

Joe: Have several floors.

GM: I didn’t mean that!

Joe: Well. My main forte is second-story burglary, but I can work with this – our plan was for me to sneak in unnoticed, but I guess it doesn’t have to be the second floor. Is there somewhere else I can sneak through? Maybe a backyard?

GM: Sure, there’s a whole garden at the back, and it’s very dark there at night.

Joe: Sweeeet.

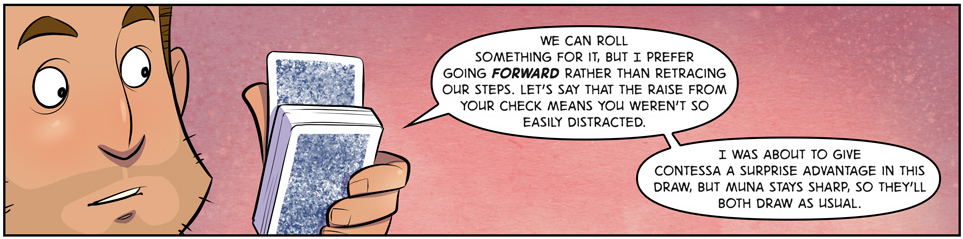

Solve by pushing forward

Generally speaking, and unless the mismatched facts are really crucial and the disagreement is fundamental, it’s best for the GM (who has the unique position of being the arbiter of what’s canon) to try and push forward by agreeing with the most interesting interpretation and using the rules in favour of the drama. Propel ever forward! Most of the time, “in favour of the drama” is working for the players, but since you should go with the most interesting interpretation, it can definitely be against them as well. Most players tend to suggest some amazingly difficult situations for their characters.

GM: Sure, they’re white and clean, and–

Joe: Have several floors.

GM: I didn’t mean that!

Amy: And there are lots of guard dogs around, right?

GM: Erm…

Amy: I mean, I spent some time in Italy, and let me tell you, they sure love their dogs. Oh, and the men tend to hang outside at night, drinking in their gardens because it’s warm and nice.

Joe: Not exactly making it easier to break inside.

GM: But interesting! Sure, we’ll go with that. But to be fair – I don’t want you to think it’s just an impossible task – the house also has a second floor.

Learn for next time

Misunderstandings will always happen, but if we stop for a second to see what happened just now, they might not happen again this way. Was the player working off some details he mentioned off-hand one time, and were super-important to him but no-one else remembered? (“My pet monkey tries to steal that” “Wait, what monkey?”) Perhaps you should all decide on making sure you keep mentioning the things you find important about your characters, even if they’re not relevant in any particular action. Did the GM try to subvert some expectations, and no one understands what the hell she wants? (“As you open the door, you see… a spaceship!” “Wait, what?”) Perhaps you should signal some things in advance – the image of the world that we keep in our mind contains some assumptions which are sort of un-facts (“there is definitely no sci-fi stuff in this fantasy world”) as well as facts.

These understandings are based on Gil Ran’s excellent series about “spaces” – personal, interpersonal, imaginary and others – that exist in RPGs. The articles are available in Hebrew, and hopefully soon in English as well.