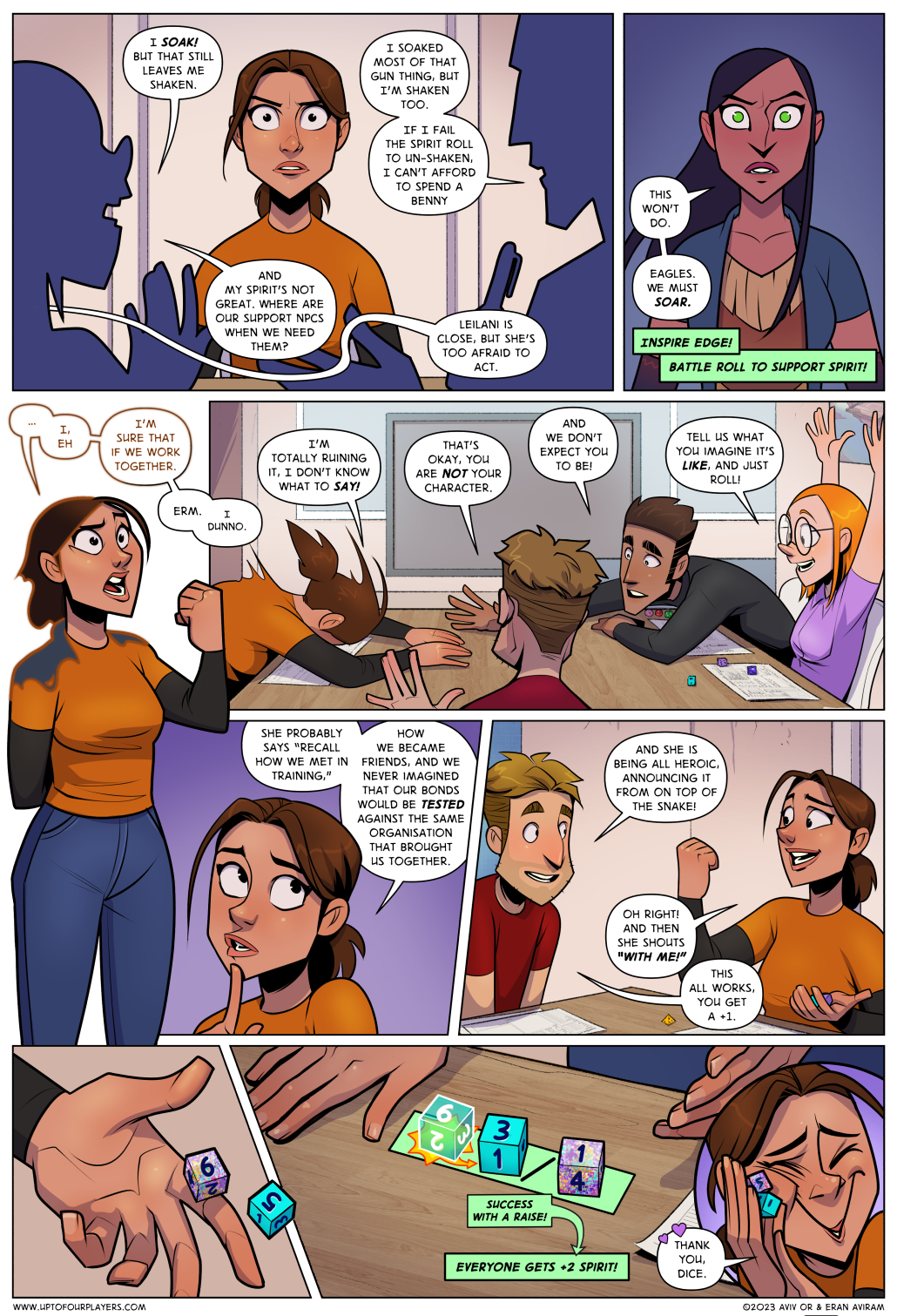

Listen. Portraying your character is not required.

Even if you’re the sort of person who comes to the table specifically so you can feel like a Maseian princess, sometimes you have an off evening, or you’re hungry, or you’re too focused on the mechanics of the fight and what to do next turn, or maybe all three. It doesn’t matter, because you don’t owe portraying your character to anyone, including yourself.

There are (still, and always will be) voices who say that in “roleplaying games you should roleplay, obviously“. But there’s a misunderstandings of definitions here, one of several reasons why I prefer using more precise terms. Once we cut down into what roleplaying is, it becomes self-evident that those voice literally don’t know what they’re saying.

(I’m doing my best to ignore the “should” in that sentence, because that would lead us to a “you’re having fun wrong” discussion, which is for another time).

In my professional capacity as a Person Who Does RPG Stuff I avoid using the term “roleplaying games”, except for in the most vaugests of needs, like when I describe my job to someone from outside our niche. For a professional use, I find that identifying the elements of a game is much more useful than trying to put the whole game into a specific category. We gain little from trying to put things into boxes; things are nuanced.

Fiasco, or For the Queen, are prime examples – they obviously have roleplaying elements (you play a role), and yet, many people would say they’re a storytelling game first (including their own descriptions; neither describes itself as an RPG). They’re both gm-less, structured narrative experiences, aimed at creating a specific story. The games use character portrayals mostly as an improv tool, in the service of the story it wants us to tell. In a classic roleplaying game, it’s almost the other way around. (Of course, in a technical discussion I would rather not say “storytelling game” as well, rather “storytelling elements”).

RP elements are, basically, “when you’re like someone else”. The one we usually think about is “portraying an imaginary person”. But, more importantly, it includes “thinking like an imaginary person”. The two don’t have to happen at the same time, and actually, the acting part doesn’t have to happen at all, because it’s the “thinking like” that’s core – the portrayal hinges upon it.

In other words, in roleplaying games we should* believe ourselves to be a person other than ourselves; however we then behave around the table matters less.

(*in order to maximise the fun potential, assuming this is a motivation we have and enjoy)

We want to have fun, but we are human, and therefore unable to fully achieve our goals every time. When we arrive at a moment in which one of the participants in the game has some great intentions but lacks the ability to follow through, everyone else should help; we’ve seen this for two pages now, from different perspectives. Both a game’s rulebook and the general gaming culture should provide each group with the mindset and tools the establish an environment in which this line of thinking is common sense.

These days, Lines and Veils is entering the gaming culture as a tool so basic it begins to border on the obvious, and I think the next step would be to expand the discussion about safety tools beyond safety, and into comfort.

Also, how cool is Savage Worlds that “making a rousing speech to raise spirits” is a valid, optimal combat move.